Lance and I have had an early morning call, rain or shine, warm or cold, most weeks for the past 3 years. No topic is off limits and the general focus of our calls is catching up and talking through what’s on our mind.

I’ve found conversations with friends to be great places to develop and test ideas. As Lance and I were talking recently, several topics that have been on my mind over the past few weeks came together and over the course of the call we developed our first take on the relationship between luck, skill, and effort.

The Hypothesis

In the human experience, I posit that luck, skill, and effort are related.

As I explored the idea further after that conversation with Lance, I thought about why I found this topic interesting. That lead me to thinking about how we define “success” and a hypothesis:

Success in life is the skill to navigate luck events in a way that’s aligned with what you value.

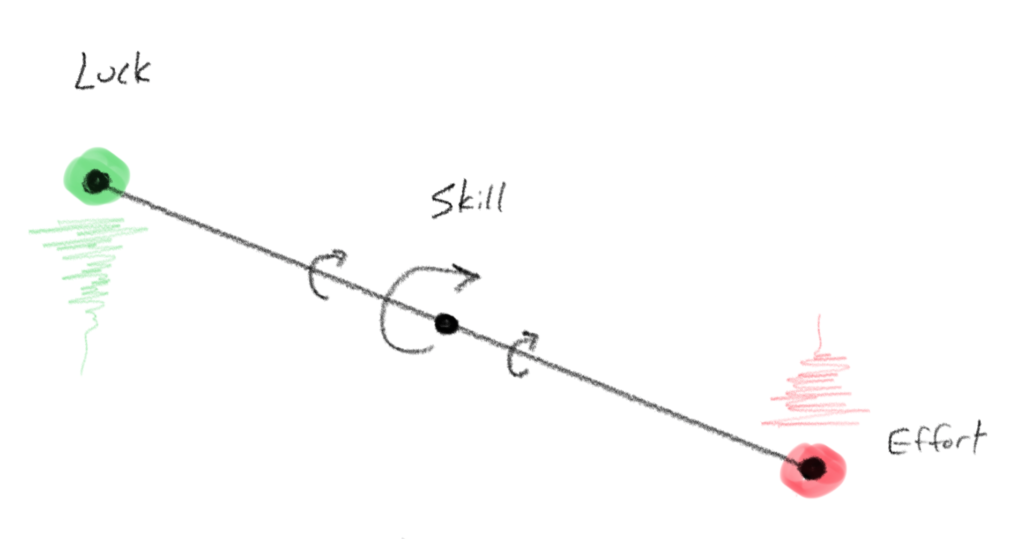

Imagine luck and effort on opposite sides of a line rotating slowly in place. This line represents your life, moving forward, rotating slower or faster as it moves in and out of balance.

Skill influences that balance. As skill increases with each rotation, so in turn does the ability to influence balance. Also, as an added bonus, the speed of rotation increases as the line approaches balance, representing a faster rate of skill development.

Success in the journey of life, then, is the skill through which you navigate all that life sends you in a way in that’s aligned with what you value which, as we’ll explore, is what determines the effort you’re willing and able to expend.

Luck

As illustrated in the story of the man who lost his horse, I find that the line between “good luck” and “bad luck” is fuzzy at best and what we can all agree on is that luck happens.

Luck is outside of our control. Luck events determine where, when, and to whom you’re born. Luck events shape the environment in which you work and live. Luck impacts the entire human experience, bringing joy and sorrow, life and death.

Jim Collins in Great By Choice introduces the concept of Return On Luck, which he summarizes as follows:

Our research showed that the great companies… got a higher return on luck, making more of their luck than others. The critical question is not, Will you get luck? but What will you do with the luck that you get?

In our personal lives, the same idea follows and I suggest that the skills we develop are what determine our ability to navigate the luck that happens to us.

Skill

A skill is your ability to take an action, to do something. We each have tens of thousands of skills that we inherit and develop, including mental, emotional, relational, and physical skills. Your skills are deeply intertwined with who you are.

Skills that stand out to me include:

- Prioritizing – Making a decision about what matters.

- Envisioning – Being able to imagine what’s possible.

- Listening – Paying attention and inferring, then confirming, what matters.

- Asking Questions – Letting curiosity lead you.

- Letting Go – Being OK with where questions lead.

Some, none, or all of those skills may be relevant to you and we’re each going to have thousands more at various levels of development.

I also posit that the vast majority of skills we develop are subconscious and, for most of us, are first rooted in survival. For instance, from a young age I became quite good at avoiding what I had learned was “bad” for me. I also developed optimism as the lens through which I viewed the world, which helped me keep moving forward.

The skills we have, conscious and subconscious, are the tools available to us to navigate all that life sends our way.

It takes luck and effort to develop new skills and, in turn, your skills influence how you respond to luck events and the amount of effort required.

Effort

Effort is the intentional exertion of energy—physical, emotional, mental, and beyond—toward an action. The effort we invest is directly tied to how motivated we are – what we believe is worth the effort.

A parent will exercise extraordinary, physics-defying effort to save the life of their child. The same parent might not bother to even look up from the couch after the umpteenth request for their attention.

Understanding motivation has been a lifelong interest, from my early parroting of time management insights, to my more recent thoughts on going with the flow.

In more recent years, what I’ve noticed is that the clarity and depth of motivation has a strong influence on what I’m actually willing to do and how much effort I’m willing to invest.

Motivation determines effort. If I’m sufficiently motivated, I’ll invest the effort to acquire and apply the skills to the luck events, positive and negative, that come my way.

What informs motivation then? For most of my childhood and adult life, motivation was informed by a need to survive, which I successfully masked (at least to my self), by looking at life through the lens of optimism – everything was going to work out great.

As I’ve begun to move out of survival mode over these past few years I’ve found my motivation shifting. I was less willing to just “make myself” do things. I wanted less striving in my life and more calm.

What I valued had changed and in reflecting on it all over the past few weeks it hit me. Values are what inform motivation. Survival is a core value and for most of us will remain a top priority – a threat to your survival will motivate action, as it should. Beyond survival, though, the field of potential motivation is wide open.

Values

When we first start out in life, our values are influenced by our environment and especially our caregivers. Our values become our lens through which we evaluate the world and make decisions about what matters to us, including what skills we develop.

At least in my experience, I find a discussion about personal values made only as productive as my ability to be honest with myself – which is harder than you might think. As evidenced by much of my early writing, I invested significant effort into convincing myself about what mattered to me, and I was quite good at it.

Inevitably, though, I’d end up frustrated as the thing I said I valued (e.g. being efficient with my time and having todo lists) conflicted with something I actually valued (e.g. autonomy, and not being told what to do).

I think I am more capable of being honest now than I was a few decades ago and I thought it might be helpful to take a fresh look at what I believe that I value.

Here’s what stands out to me today:

- Autonomy – It remains important to me to do what I want, when and where I want to, according to my level of motivation. I’m fairly sure there’s some deep rooted beliefs at play that have their own benefits and tradeoffs. I also think this is a fairly universally human value.

- Calm – Over the past few years, perhaps somewhat in response to the prior decades, I’ve grown to value calm. I find this connected with the idea of going with the flow and in the work I continue to do to learn to “let go” and not try to figure everything out. I consider this a new value that’s become a high priority.

- Learning – From an early age, I was in an environment that cultivated curiosity (thanks Mom!). I read encyclopedias for fun as a pre-teen and the pace only picked up from there. Today, I love learning new things and developed an increasing comfort with the discomfort associated with being a beginner in a new area.

- Solving Problems – I love figuring things out. I suspect this is at the heart of my love for games of all sorts, why my interest in a game quickly fizzles when it’s “solved”, and why I keep coming back to favorite games that aren’t readily solved. I’ve found this value particularly helpful in business.

- Relationships – I did not grow up with healthy attachments and up until the past few years even, understanding the value of relationships has been a struggle. Thanks to therapy, hard work, a lot of growth through pain, and people who love me, I’ve made real progress here and relationships have moved up to become something I now deeply value.

If you haven’t lately, I encourage you to give your own values thought.

Considering the five above, what I’ve found is that when one or more are in play, my level of motivation increases. When my motivation increases, so does the level of effort I’m willing to apply to the skills I have and to developing new skills.

Conclusion

Luck, skill, and effort are related. Luck events happen and while our skills influence how we respond to them, the level of effort we’re willing to apply to current and new skills is determined by our level of motivation.

For me personally, my conclusion is to seek clarity on what I value. Being clear on what I value becomes a source of motivation for me and gives me the fuel to apply effort to the skills I have today and to developing new skills.

Luck events brought Lance and I into contact originally. Valuing relationship, though, is what kept us both motivated to continue to invest effort into building a friendship – which is its own skill. And so it goes.

Special thanks to Lance Robbins for our weekly conversations, to Nate Stewart for helping me refine the ideas further, and for Amanda Macumber for reviewing and inspiring me . ChatGPT 4o was used for refining ideas, the prose and foibles are all my own.